Two BIG Reasons NOT to keep your cash in the bank

Two BIG Reasons NOT to keep your cash in the bank

By Mark Nestmann • March 15, 2016

It’s bad enough depositing your money into a bank account and earning essentially zero interest on it, or in some countries, having a negative interest rate.

It’s even worse knowing that once you deposit your money in a bank, it’s not really yours anymore. You have turned over your property to the bank in return for a debt claim. You become an unsecured creditor holding an IOU.

Worst of all, there’s the “bail-in,” which we all became familiar with during the 2013 banking collapse in Cyprus. Some uninsured depositors got half of their money back, although at one bank, customers received nothing of their deposits over the “insured” amount.

In 2014, the leaders of the Group of Twenty (G20) – representing the world’s 20 largest economies – declared the Cyprus model should apply globally. They did so in a mind-numbing tome entitled Adequacy of Loss-Absorbing Capacity of Global Systemically Important Banks in Resolution.(http://www.fsb.org/2014/11/adequacy-of- ... esolution/)

Deposits in banks that are “too big to fail” will be promptly recapitalized with their unsecured debt. And… guess what? The largest chunk of unsecured debt is your bank deposits. Insolvent banks will recapitalize themselves by converting your deposits into worthless bank stock. This avoids taxpayer-funded bailouts that proved politically unpopular during the last financial crisis.

Oh, and get this… the G20 has also declared that derivatives – the toxic contracts Warren Buffett calls “financial weapons of mass destruction” – are secured debts. Since your bank deposits are only unsecured debt, guess who gets your money if the bet goes the wrong way for the bank? Answer: It’s not you.

Heads, the bank wins. Tails, you lose.

It’s practically guaranteed, too, that in the next financial crisis, there’ll be a whole slew of bank failures. That’s despite the fact that the mainstream financial media assures us that central banks have imposed higher capital requirements, stress tests, etc., on banks to ensure that when the “big one” hits, your deposits will be safe.

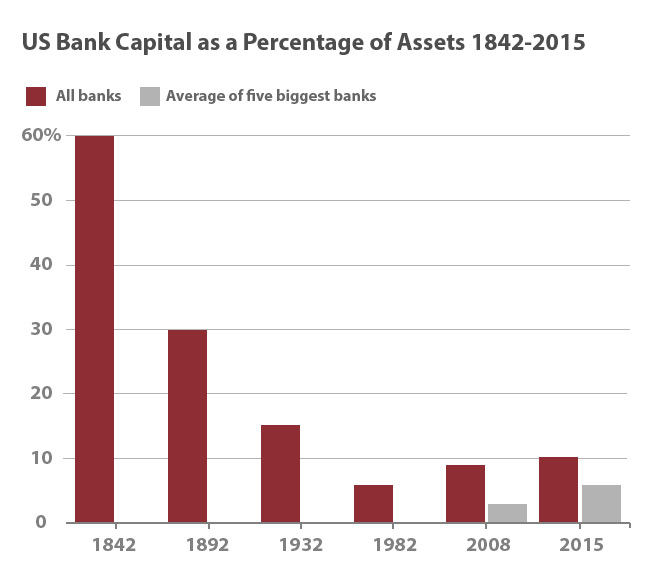

Don’t believe a word of it. The amount of capital that banks hold compared to the money on deposit is frighteningly low. In the US, the five largest banks have a capital ratio as a percentage of assets of only 6% – although that’s double what it was in 2008. In effect, if every depositor in a bank demands their money back simultaneously – the classic “bank run” – the largest US banks could repay only six cents on the dollar before they ran out of money. And since most banks don’t keep a lot of cash on hand, it could even be less.

It’s worth remembering that historically, US banks were much better capitalized. For instance, in 1842, US banks had an average capital ratio of 60% – ten times that of the largest banks today. That was an era in which bank competition was based on safety, because no deposit insurance was in effect.

This chart from Bloomberg News says it all:

Sure, in many countries your bank deposits are “insured.” In the US, the first $250,000 in your account qualifies for deposit insurance through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). But for every $100 on deposit, the FDIC has only $1.06 with which to back it. Doesn’t that make you feel warm and fuzzy about the safety of your bank deposits?

Indeed, there’s only a single type of bank that would be completely safe: one where 100% of each depositor’s funds are kept in reserve as cash or other highly liquid assets. The bank would offer conventional checking accounts for a monthly fee but hold no assets other than cash, gold, etc., in its vault.

Mainstream economists hate this idea, because the deposits couldn’t be lent out. They argue that businesses would find it much more difficult to obtain financing; homebuyers wouldn’t be able to get mortgages; etc. The economy would collapse into depression.

Frankly, I don’t buy this argument. With online peer-to-peer lending services proliferating, even in a world of 100% reserve banking, individuals and businesses will be able to obtain financing. Moreover, peer-to-peer lending services often offer lower interest rates than banks. Far from collapsing, the economy would prosper.

In any event, we’re about to find out if I’m right or wrong.

Central banks and mainstream economists thought negative interest rates and worldwide bail-in policies would encourage consumers to invest in riskier assets and businesses to borrow more, thus stoking the global economy.

That didn’t happen. Instead, the demand for cash has gone through the roof, along with secure places to store it. In Japan, which instituted negative interest rates last year, one popular brand of safe is sold out. In Switzerland, circulation of the 1,000 franc note – worth about US$1,000 – increased 17% in 2015 after the Swiss National Bank imposed negative interest rates.

This behavior deeply disturbs the powers that be. In response, they’ve imposed stricter and stricter controls on cash. I wrote about those controls in this essay from 2015, and since then, it’s only gotten worse.

Of course, your friendly central banker will never tell you it wants to abolish cash so that you have no alternative but to keep all your money in a bank where your deposits can be bailed in at the click of a mouse. Instead, the motivations are loftier – specifically, to “fight crime” and “facilitate tax compliance.” For instance, former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers wants a global ban on notes worth more than $50 or $100. He claims the linkage between high denomination notes and crime is totally convincing.

I must admit to feeling some sympathy for central bankers. In response to lagging economic growth worldwide, they’ve been forced to innovate in ways that have never been tried before. Negative interest rates and bail-ins are just two examples.

It hasn’t worked. Most people are rational and respond to adverse financial incentives (like negative interest rates) by doing whatever they can to preserve their capital. They hoard cash, buy assets like gold that can’t be bailed in, and move their money to the safest possible banks.

If you haven’t already done so, maybe you should consider joining them.

Mark Nestmann

Nestmann.com

By Mark Nestmann • March 15, 2016

It’s bad enough depositing your money into a bank account and earning essentially zero interest on it, or in some countries, having a negative interest rate.

It’s even worse knowing that once you deposit your money in a bank, it’s not really yours anymore. You have turned over your property to the bank in return for a debt claim. You become an unsecured creditor holding an IOU.

Worst of all, there’s the “bail-in,” which we all became familiar with during the 2013 banking collapse in Cyprus. Some uninsured depositors got half of their money back, although at one bank, customers received nothing of their deposits over the “insured” amount.

In 2014, the leaders of the Group of Twenty (G20) – representing the world’s 20 largest economies – declared the Cyprus model should apply globally. They did so in a mind-numbing tome entitled Adequacy of Loss-Absorbing Capacity of Global Systemically Important Banks in Resolution.(http://www.fsb.org/2014/11/adequacy-of- ... esolution/)

Deposits in banks that are “too big to fail” will be promptly recapitalized with their unsecured debt. And… guess what? The largest chunk of unsecured debt is your bank deposits. Insolvent banks will recapitalize themselves by converting your deposits into worthless bank stock. This avoids taxpayer-funded bailouts that proved politically unpopular during the last financial crisis.

Oh, and get this… the G20 has also declared that derivatives – the toxic contracts Warren Buffett calls “financial weapons of mass destruction” – are secured debts. Since your bank deposits are only unsecured debt, guess who gets your money if the bet goes the wrong way for the bank? Answer: It’s not you.

Heads, the bank wins. Tails, you lose.

It’s practically guaranteed, too, that in the next financial crisis, there’ll be a whole slew of bank failures. That’s despite the fact that the mainstream financial media assures us that central banks have imposed higher capital requirements, stress tests, etc., on banks to ensure that when the “big one” hits, your deposits will be safe.

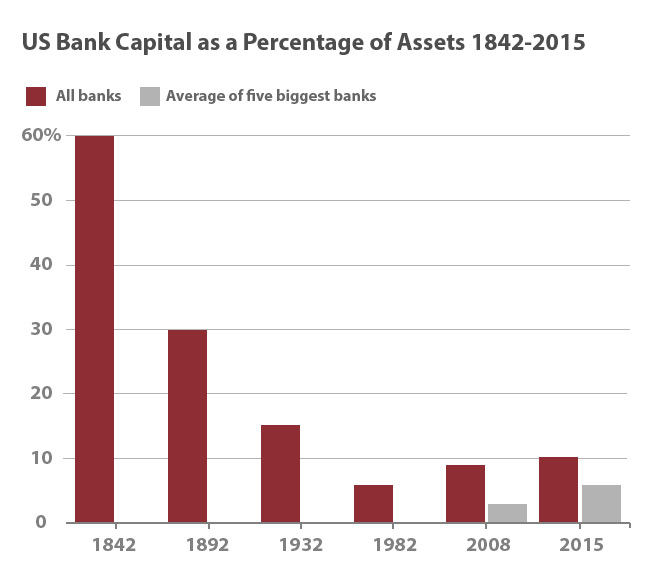

Don’t believe a word of it. The amount of capital that banks hold compared to the money on deposit is frighteningly low. In the US, the five largest banks have a capital ratio as a percentage of assets of only 6% – although that’s double what it was in 2008. In effect, if every depositor in a bank demands their money back simultaneously – the classic “bank run” – the largest US banks could repay only six cents on the dollar before they ran out of money. And since most banks don’t keep a lot of cash on hand, it could even be less.

It’s worth remembering that historically, US banks were much better capitalized. For instance, in 1842, US banks had an average capital ratio of 60% – ten times that of the largest banks today. That was an era in which bank competition was based on safety, because no deposit insurance was in effect.

This chart from Bloomberg News says it all:

Sure, in many countries your bank deposits are “insured.” In the US, the first $250,000 in your account qualifies for deposit insurance through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). But for every $100 on deposit, the FDIC has only $1.06 with which to back it. Doesn’t that make you feel warm and fuzzy about the safety of your bank deposits?

Indeed, there’s only a single type of bank that would be completely safe: one where 100% of each depositor’s funds are kept in reserve as cash or other highly liquid assets. The bank would offer conventional checking accounts for a monthly fee but hold no assets other than cash, gold, etc., in its vault.

Mainstream economists hate this idea, because the deposits couldn’t be lent out. They argue that businesses would find it much more difficult to obtain financing; homebuyers wouldn’t be able to get mortgages; etc. The economy would collapse into depression.

Frankly, I don’t buy this argument. With online peer-to-peer lending services proliferating, even in a world of 100% reserve banking, individuals and businesses will be able to obtain financing. Moreover, peer-to-peer lending services often offer lower interest rates than banks. Far from collapsing, the economy would prosper.

In any event, we’re about to find out if I’m right or wrong.

Central banks and mainstream economists thought negative interest rates and worldwide bail-in policies would encourage consumers to invest in riskier assets and businesses to borrow more, thus stoking the global economy.

That didn’t happen. Instead, the demand for cash has gone through the roof, along with secure places to store it. In Japan, which instituted negative interest rates last year, one popular brand of safe is sold out. In Switzerland, circulation of the 1,000 franc note – worth about US$1,000 – increased 17% in 2015 after the Swiss National Bank imposed negative interest rates.

This behavior deeply disturbs the powers that be. In response, they’ve imposed stricter and stricter controls on cash. I wrote about those controls in this essay from 2015, and since then, it’s only gotten worse.

Of course, your friendly central banker will never tell you it wants to abolish cash so that you have no alternative but to keep all your money in a bank where your deposits can be bailed in at the click of a mouse. Instead, the motivations are loftier – specifically, to “fight crime” and “facilitate tax compliance.” For instance, former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers wants a global ban on notes worth more than $50 or $100. He claims the linkage between high denomination notes and crime is totally convincing.

I must admit to feeling some sympathy for central bankers. In response to lagging economic growth worldwide, they’ve been forced to innovate in ways that have never been tried before. Negative interest rates and bail-ins are just two examples.

It hasn’t worked. Most people are rational and respond to adverse financial incentives (like negative interest rates) by doing whatever they can to preserve their capital. They hoard cash, buy assets like gold that can’t be bailed in, and move their money to the safest possible banks.

If you haven’t already done so, maybe you should consider joining them.

Mark Nestmann

Nestmann.com